Last week’s column, we discussed cull cow grades. Remember cull cows that are destined to go to the packing house are graded by their fleshiness. The fattest cows are called “Breakers”. Moderately fleshed cows are “Boning utility”. Thin cows are called “Leans” or “Lights”, depending upon the weight of the cow. There will be price differences among these four grades.

However, within each grade, large variation in prices per hundredweight will exist because of differences in dressing percentage. Cow buyers are particularly aware of the proportion of the purchased live weight that eventually becomes saleable product hanging on the rail. Dressing percentage is (mathematically) the carcass weight divided by the live weight multiplied by 100. For instance, a cow with a 1,400 lb. live weight and a “hot carcass” weight (once they have been eviscerated, and the hide, feet, and head removed) of 650 lbs. has a Dressing Percent of 46% (650/1400 = .4642 x 100 = 46%)

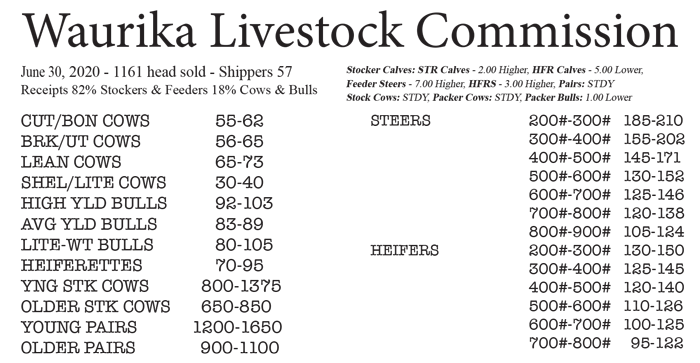

Key factors that affect dressing percentage include gut fill, udder size, mud and manure on the hide, excess leather on the body, and anything else that contributes to the live weight but will not add to the carcass weight. Obviously, pregnancy will dramatically lower dressing percentage due the weight of the fetus, fluids, and membranes that will not be on the hanging carcass. Most USDA Market News reports for cull cows will give price ranges for High, Average, and Low Dressing Percentages for each of the previous mentioned grades. As you study these price reports, note that the differences between High and Low Dressing cows and bulls will generally be greater than differences between grades. Many reports will indicate that Low Dressing cows will be discounted up to $8 to $12 per hundredweight compared to High Dressing cows and will be discounted $5 to $7 per hundredweight compared to Average Dressing cows. These price differences are “usually” widest for the thinner cow grades (Leans and Lights). See examples from last week’s sale in the Oklahoma City National Stockyards: http://www.ams.usda.gov/mnreports/ko_ls151.txt

As producers market cull cows and bulls, they should be cautious about selling cattle with excess fill. The large discounts due to low dressing percent often will more than offset any advantage from the added weight. They should also be cautious about selling old, “broke mouth” or “smooth mouth” cows that are pregnant but not likely to be purchased by someone intending to take them to grass.

Cull cow prices are typically lowest in the fall, as many producers sell cull cows immediately after weaning. The cull cow market exhibits consistent seasonality across years, as evident in the graph below, where prices in March and April are approximately 15 index points higher than prices in October and November. Though the market price levels have seen unusual increases in more recent years, the seasonal pattern has persisted. This seasonality offers opportunities to deviate from traditional fall marketing of cull cows and potentially increasing salvage value by retaining cows into the spring months to market during seasonal high prices (Feuz 2010; Peel and Meyer 2002; Yager, Greer and Burt 1980). Many factors influence this decision, including individual cow health, potential weight gain, cash flow needs, on-farm resources for retention and feeding, current market conditions versus market expectations and time. In addition to feed costs, the decision to retain cull cows requires more labor and management time, including feeding cows, separating culls for possible rebreeding and pregnancy checking. Facilities and pasture availability are important considerations as well, since cull cows on feed are likely managed as a group separately from the breeding herd. Not considered here is the fact that retaining cull cows utilizes forage resources that might be used for another cattle enterprise, either more brood cows or stocker cattle. On the other hand, feeding culled cows may be a good way to capture the value of excess or leftover pasture or hay that may not otherwise get utilized or have a better use. Ultimately, the marketing decision has implications for the individual cow’s salvage value and the producer’s bottom line.

Seasonal Price Index for Utility (Slaughter) Cows, Southern Plains, 2004-2013. Data Source: USDA-AMS, Compiled & Analysis by LMIC Livestock Marketing Information Center.

Find out what’s happening on the Oklahoma Cooperative Extension Calendar at https://calendar.okstate.edu/oces/#/?i=2

Follow me on Facebook @ https://www.facebook.com/leland.mcdaniel

Oklahoma State University, in compliance with Title VI and VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Executive Order 11246 as amended, and Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972 (Higher Education Act), the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990, and other federal and state laws and regulations, does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, national origin, genetic information, sex, age, sexual orientation, gender identity, religion, disability, or status as a veteran, in any of its policies, practices or procedures. This provision includes, but is not limited to admissions, employment, financial aid, and educational services. The Director of Equal Opportunity, 408 Whitehurst, OSU, Stillwater, OK 74078-1035; Phone 405-744-5371; email: eeo@okstate.edu has been designated to handle inquiries regarding non-discrimination policies. Any person who believes that discriminatory practices have been engaged in based on gender may discuss his or her concerns and file informal or formal complaints of possible violations of Title IX with OSU’s Title IX Coordinator 405-744-9154.